Painting and sculpture

The genesis of abstract painting. The first exhibitions.

As Arnaldo Ginna stated in many of his written works, the genesis of his painting and his artistic, scientific and philosophical interests can be traced back to his formative years in Ravenna.

Ginna’s artistic upbringing was mainly academic and his early paintings showed he was still interested in artwork of the 19th century mostly with a social content. However, his interests soon focused more on painting techniques and the use of colour.

The issue, that the young artist poses himself from the start, is the search for spirituality in art: where could one find it among the artists of the past and how could one find it again in order to repropose it in the present using a new language? He is fascinated by the Byzantine art of the Ravenna mosaics:

“… the true starting point of art… the beginning of the descent of human spirituality towards the sensitive world.”

Thanks to a first trip to London and Paris, he became aware of the art of the Impressionists, and explored it: in particular he noticed Van Gogh’s innovative use of colour and Cézanne’s new pictorial reality. He is deeply interested in Kubin, the painter of the invisible and his effort to give figure to the ultrasensitive. In Italy, he is certainly also familiar with the drawings of Romolo Romani and with the graphic externalisations of moods in his works. Subsequently, after wandering around the Florentine museums and observing ‘the canvases of the greatest painters’, he began to search for a meaning that encompassed and explained the very magic of art, looking for a common point in his artistic research eventhough the times and ways had changed remarkably. This is how Ginna explained the genesis of his abstract painting:

“While at the Academy of Fine Arts I copied plaster statues with charcoal, while at home I messed around with pure colours on pieces of cardboard and wood. They were mostly outbursts of colour, as they were done without any fixed goal other than for my pure enjoyment, while whistling away. Meanwhile, I was beginning to understand the connection between the paintings of Raphael and Leonardo and the mosaics of the Byzantine churches in Ravenna. The subject matter was not important, nor the medium used, it all depended on the harmony and expression of the colours, chiaro-scuro, hence chromatic music. In 1908, I had a break down, and was bedridden, I then experimented with colour-only painting with coloured pastels, which later gave me the opportunity to create my first truly abstract painting, Neurasthenia: a state of mind expressed with colours alone. Then, the following year in 1909, I did another abstract painting, Romantic Walk.”

In 1908, the painter was only eighteen years old but his experiences anticipated those of the great European artists who would create, shortly afterwards and in other ways, works of pure abstraction. Ginna painted states of mind, in pure thought and pure colour, that resulted from a profound search for inwardness. In his theoretical writings, Ginna calls this chromatic painting and pictorial work; chromatic chords. As in a musical chord, the harmony of colours that occupies the space of the painting develops symphonically to give rise to chromatic music that conveys the passion of the artist-creator, his moods, his hidden feelings.

Roma, collezione privata.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

The following years are dedicated to experimentation in the attempt to create the chromatic drama, the union of music – painting – literature, in theatre and cinema, with the invention of a ‘chromatic piano’, a keyboard to which coloured lights were connected to be projected on stage, and later with the application of colour directly onto film. These attempts are documented in Bruno Corra’s text Chromatic Music of 1912. In May 1911, Ginna exhibited some works at the Faenza Art Exhibition. The catalogue shows three cacardboards for ceramics and two drawings: Ritratto di Balilla Pratella (Portrait of Balilla Pratella) and Le visioni di un cieco nato (Visions of a man born blind), works that have unfortunately been lost. This is the first time he participated in an exhibition with his almost certain non-figurative works and, as certified in his following letter to Pratella, it had not been easy:

“My participation at the Faenza exhibition became known; it was almost a scandal for Ravenna and even more so for my peers as well as the professors etc… “one must study more than that “guardè pu i le, di burdel chi s’arvena perché quelcadon sià scaldè la testa”. (See Futurism and companions). One will see what I am aiming for in both painting and sculpture, what is certain is that I will have to come up against many obstacles and I will have to experience many disappointments… what does it matter when I am sure that I can do more than anyone else! Today’s childish games will be tomorrow’s monuments.”

The next exhibition that Ginna took part in from December 1912 to January 1913, was the Esposizione di bozzetti di pittura e scultura at the Società delle Belle Arti in Florence. The two works he exhibited were Nevrastenia from 1908 and Passeggiata Romantica (Romantic Walk) from 1909, placed in the section dedicated to ‘drawing room decorations’

“… more was needed at this time to explain the true content of abstract painting.”

Futurist painting and Futurist exhibitions.

With this wealth of new ideas and artistic theories Ginna introduced himself to the Futurist general staff in Milan approxikately in 1912. This historic meeting gave rise to a lively debate on how to understand the dynamism of time and space in painting, which, according to the Futurists, stemmed from movement and speed, while for Ginna, from the inner motions of the spirit, and the states of mind.

“From the animated discussion Carrà and Russolo were able to remain on their view points, however, this was not the case for Marinetti and Boccioni who validated some of our ideas on Chromatic Music free of all geometric graphics. In this debate, we only reached agreement on the one painting entitled ‘State of Mind’, and in so saying, we remained distant in the ways we expressed this ‘State of Mind’. Boccioni had a sensitive state of mind. Ginna was supersensitive.”

The discussions that further arose from this exchange had important effects: it was a subject of great interest for Umberto Boccioni as well for Giacomo Balla, the two leading souls of Futurist painting, and, coincidently, both were fascinated by parapsychology and occultism. This research merged into the more spiritual and animistic current of Futurism in contrast (but not in antithesis) with the machinist and machinocentric current.

In 1914, Ginna was invited by Boccioni, thanks to Balilla Pratella, to participate in the International Futurist Free Exhibition in Rome at the Sprovieri Gallery from 13 April to 25 May, 1914.

The material that arrived in Rome, for the exhibition, was abundant and varied: it was a unique opportunity that allowed many young artists, some of them at their first exhibition, to appear alongside the great Italian and European names. Among others are Archipenko and Kandinsky. Giuseppe Sprovieri wrote to Ginna years later:

Roma, collezione privata. “Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

“…at once you appeared with your works that were linked to what was just emerging, by the two previously mentioned artists, [Archipenko and Kandisky]and about to take shape, precisely in the the strain to react to reproduction, with the creation of new forces that had very little in common with the truth, that is to say with the start of abstractionism. This became clear to us and was the main subject of our discussions. We noticed how you wanted to escape from the representation of reality by means of a musical transfiguration at the very moment the boxes were opened. That is to say, by means of equivalents no less than Kandinsky had… similarity is meant in terms of inspiration and conception and therefore not formal as an imitation.”

Ginna exhibited six works at the exhibition: Paganini (fantastic expressive synthesis), Edgar Poe (fantastic expressive synthesis), The Music of Dance (theme of a symphony of colours), Rhythms shapes and colours of an open window awakening, Lust (chromatic chord), Intoxication.

Some of these works have been lost, but we have a description of Paganini by Ginna himself. It would appear to be an “animic portrait” in accordance with the type of portraits that the painter also produced later, trying to specifically represent the spirit and soul of the person portrayed, pictorially halted in a “fantastic expressive synthesis” created thanks to a psychoanalytic use of colours. A work that is almost painted in an unconscious state or trance (of ‘conscious subconscious) probably also induced by use of drugs:

“I plunged into an unconscious state for twelve hours with a habitual medium. For twelve hours I worked on the canvas. I was a whirlwind of colours and ideas; I had to weld them together and lay them on the bench. Some ideas were getting lost. Some colours were exploding. I felt suffocated…. To me, it seems like there is a bit of Paganini’s soul now dissolved in the green, yellow and purple. I study the fumes. Could it be steam?”.

We have the following description by Marinetti, also of Lust, probably a tactile tableau that apparently fascinated actress Eleonora Duse,

“Pictorial, but also a tactile, tableau that offered its seductive and fascinating red satin padding to the hands of the public in a horizontal position, achieving the effect of an infinite palpable variety of carnal pleasures”.

These were peculiar and revolutionary works, that did not appeal to everyone, in fact they were considered ‘literary’ in contrast to the Futurist idea of forever freeing art from cerebrality. In a letter from Prampolini to Boccioni, the accusation is even harsher:

“How can I free myself from the amateurism of some amateurs who invade this young Futurist Free Exhibition? I also spoke to Marinetti about my hesitation to exhibit works when I saw the compositions of others that declared they did not want to be Futurists, like Corradini for example, and so many other synaesthetes, cubists, and dull amateurs.”

Here is how Ginna responded, years later, in one of his writings:

“Prampolini was quite right…. It’s true! I didn’t feel like a Futurist painter at all, if by pictorial Futurism we intend expression by the use of cubes, triangles, straight lines, mechanical shadings etc. that are well known to connoisseurs of plastic dynamism. Only later, thanks to a special rapprochement between Boccioni and I, was I able to call myself a futurist in the sense that my past pictures became the future’.”

Also in 1919, Ginna participated in the Great National Futurist Exhibition, in Milan and then in Genoa and Florence, where he exhibited the works Paganini and Lussuria and, probably, a composition of cushions.

Ginna’s last known participation in a Futuristic exhibition was at the International Futurist Exhibition at the Winter Club of Turin in 1922, where he exhibited three works of which no trace has been found to this day: La madre pazza (The Mad Mother), L’assassino (The Assassin) and L’Idiota (The Idiot), which, according to their titles, would appear to be an analytical study of the world’s degeneration, three researches into disfunctional behaviours of the mind, mediated by Lombroso’s studies but then, perhaps translated into ‘animic’ portraits in which colours and lines define the different states of the human mind and soul.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

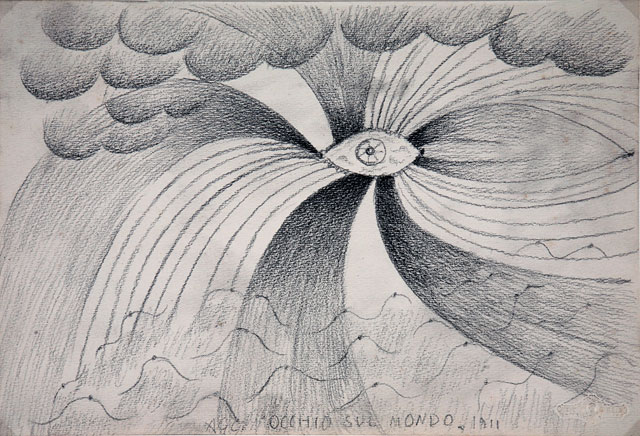

Occult painting. animic portraits. musical painting or painting of the invisible.

In 1915, Ginna wrote the theoretical text Painting of the Occult, which was republished in 1917. In it, the artist demonstrated that he had fully matured the concept of the unreal, non-representational painting, which he called ‘occult painting’ or ‘painting of the supersensitive’ and claimed the role of theorist of this new art, which goes beyond the abstract. It is a very important text for the understanding of the pictorial choices that Ginna would make in the following years. A painting that ‘precedes science’ and develops in the subconscious:

“The sub-conscious state is not an unconscious state at all, but instead superior- conscious; it is consciousness and knowledge of a more distant, more hidden and occult truth.”

Ginna became increasingly fascinated by Rudolf Steiner’s beliefs to the point of focusing all his studies on him. Moreover, after the Austrian philosopher founded the Anthroposophical Society, his writings delved more deeply into themes related to art and the Christian religion. In particular, Ginna finalised his artistic production, and began painting a transposition of Steiner’s themes, using visual art as a means to achieve knowledge of the supersensitive. His frequent visits with the painter Giacomo Balla are often meetings designed to discuss and deepen these themes. Here, he also met the young Julius Evola:

“Evola painted an abstractionism of the state of mind very similar to how I did it, with a hint of the occult, animic feeling … At a certain point, however, I found that my tendencies diverged from Evola’s. Evola tended towards the ‘superman’, I tended towards the minimal man: the empathic man; I would say the annihilation of man before God.”

His artistic maturity therefore meant a deepening of religious themes and an even greater inner analysis, which is reflected in his works during these years.

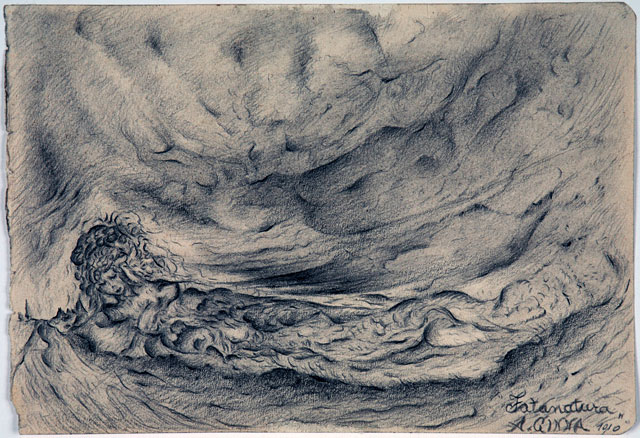

Ginna’s pictorial work never follows a single path and never delves into a single subject. Even in this period, which is most associated with the representation of avant-garde themes in painting, theoretical texts and manifestos, that in several ways were more experimental, survived, which were more intimate and less tied to extroversion.

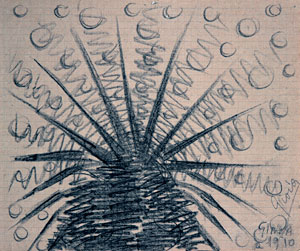

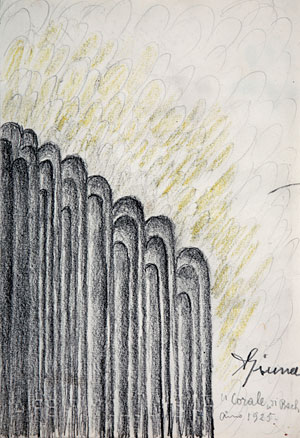

Mention has already been made of the animic portraits, the transposition into the work of art of the animic power emanated from the representation of these subjects (a person but also an animal or plant) in the form of lines and colours. Another recurring theme in Ginna’s painting is music. Here too, an abstract subject is depicted dictated by the spiritual feelings that arised from a musical piece.

Roma, collezione privata.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

Ginna called them paintings of the invisible because they conveyed a musical concept that is synaesthetically adaptable in the repetition of signs and colours in a pictorial space as it is through the repetition of sounds in time and space during a musical performance.

Illustrazioni.

Illustrations.

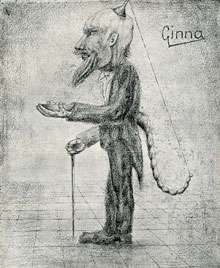

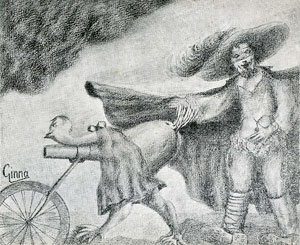

Another artistic activity that Ginna cultivated from his earliest years was that of illustrator. His first drawings on the covers of the magazine ‘Poesia’ date back to 1910 and for Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia, he had already illustrated La nuova Carmagnola from Lucini’s Revolverate in 1909. These are still symbolistic iconographies that evolve into oneiric-surreal images in the subsequent illustrations published in ‘Italia Futurista’ from 1916 to 1918. For the Edizioni dell’Italia Futurista directed by his first wife Maria Crisi Ginanni, he designed the covers of all publications including his Pittura dell’avvenire of 1917 (contact theoretical texts) and later, in 1919, for the Edizionio Facchi of Milan, once again directed by Ginanni, he illustrated Corra’s stories I Funerali di Lapa Bambi and Sam Dunn e’ morto (The funerals of Lapa Bambi and Sam Dunn is dead “. Also, in 1919, and for the same editions, he created grotesque and surreal drawings for his collection of short stories Le locomotive con le calze “Locomotives with stockings”. His work as illustrator continued in the pages of ‘Impero’, ‘Oggi e domani’ (Today and yesterday) and ‘Futurismo’ throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

illustration for Le locomotive con le calze, 1919.

Figurative painting, landscapes.

“Why shouldn’t one have different experiences at the same time? … Right from the beginning, I have made both formal and informal paintings with interjections of other pictorial outbursts, … if I want to express the nature of forms with titles such as ‘Landscape’, ‘Marina’, ‘The Pine Forest’, I must keep to the formal; but if instead I wish to express a state of mind such as ‘Cheerfulness’, ‘Hate’, ‘Neurasthenia’, etc., I must resort to abstract forms. And as one is alive, one must jump from pole to pole with the formal and the abstract… And beyond… “

This testimony given by Ginna to Mario Verdone in the 1960s reiterates an important and rather unique concept in the panorama of 20th century painting, namely that the abstract choice, unique to his painting, is not an absolute formal choice but only necessary to achieve certain representational aims. Parallel to the non-figurative production, we therefore find works in which the sensitive subject is present and clearly depicted.

Fotografia di Pietro Zigrossi. “Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

His never-ending interest in nature and the natural phenomena, studied and expressed pictorially during his holidays in Campiano as a young adult, along with his interest in nature increasingly perceived as a vital, spiritual organism, spills over into his figurative paintings, with images taken of moments from his family life in the countryside between San Gemini and Foglia Sabina and, in the summer, in the Grottammare marinas. There are drawings and small panels, hardly ever large works, almost always studies of landscapes, trees, and flowers, taken on a daily basis and always from different angles, adapting the light, weather conditions, and techniques used. With Ginna’s pencils or brush these mountains, skies, valleys, forests, trees, flowers, boats and waves come alive with their own spiritual life that emerge more or less clearly from the interpretation of the work.

Roma, collezione privata.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

Mostly in the 1940s and 1950s, portraits and landscapes were painted using more traditional methods and techniques with works that were also larger in size. And experimentation, which was never abandoned, is best found in the pencil and pastel drawings and in the small notebooks.

In these years, the only time that he exhibited to the public was at the end of 1948 in a personal exhibition in Rome, where he displayed only landscapes, openly declaring his departure from Futurist themes.

Sculptures, ceramics, furniture, stage sets.

Roma, collezione privata.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

At the academy in Ravenna, as a pupil of Professor Masserenti, and as a witness to the best school of 19th-century sculpture, Arnaldo Ginna sculpted works with a naturalistic approach and a social humanitarian connotation that reached an interesting technical level, such as the Vecchina cieca (Blind Old Woman), the only evidence left of this early production together with some photographs of similar works that have since then disappeared. There are also vague records of abstract sculptures that are assumed to have been produced by Ginna during his career, which, also, have been unfortunately lost.

However, Ginna’s eclecticism still manifested itself in other artistic activities, of which we only have photographic evidence or designs.

The catalogue of the Faenza exhibition of 1911, showed that Ginna exhibited three cartoons for ceramics, and some ceramic designs dating from the 1920s preserved among his works. Many artists, especially futurists, dedicated themselves to the production of artistic ceramics, exploiting the ductility of the material that allowed for daring compositions and exceptional possibilities of chromatic games. Moreover, Ginna’s creativity on this subject, must have been stimulated by his ife in Faenza, a city of ceramics and craftsmanship.

Ginna created his futurist furniture, for the home of the actress Diana Karenne, in the cabinet-makers’ workshops of Faenza, composed of all-precious wood, such as maple and rosewood, with gold and mosaic decorations, (reminiscent of the mosaics of Ravenna), designed for a dining room, a living room, (Egyptian sofa, armchairs), and a bedroom, (mirrors, toilet, bed, wardrobe). This was furniture in the shape of perfume bottles and party favours, as Ginna himself described it (according to Mario Verdone’s testimony), also recalling his involvement in decorating the door frames of the house of the Princess of Teano.

Roma, collezione privata.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

The activity as a designer of furnishings as well as futurist objects and clothing (pillows, ties, always testified by accounts and rare photographic images) is certainly due to his gatherings at the home of the futurist Giacomo Balla, theorist of the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe, united in friendship with Ginna and by mutual exchanges of artistic interests.

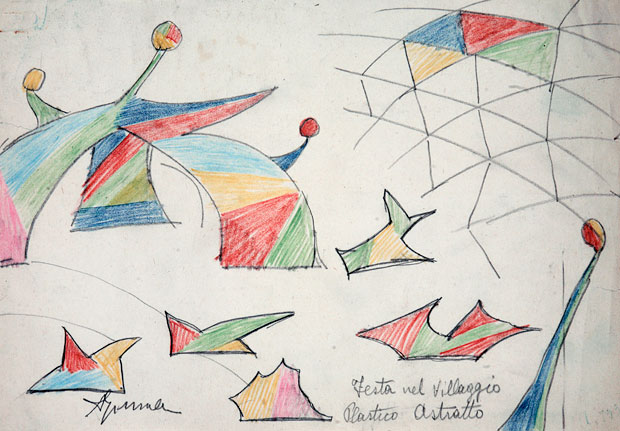

The probable design of theatre sets is instead testified by some sketches “Il solitario” (The solitary person) and Festa nel villaggio,(Party in the Village) drawn in the 1930s and then translated into two wooden models at the end of the 1950s, when Ginna’s art returned to speak a neo-Futurist language.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

Text by Lucia Collarile